City Lights bookstore is considered something of a Beatnik mecca. Tourists come from all over the world to wander around this bookstore that Kerouac, Ginsberg, and so many others called home. But as that cliché saying goes, don’t judge a book by its cover. Or in this case, don’t judge a bookstore by its reputation. Just because its history is tied up with the Beatniks, we can’t forget that first and foremost, City Lights is a bookstore, and bookstores have to pay attention to their community. City Lights has grown from their roots in the Beatnik movement to incorporate the multicultural aspects of their community in North Beach, San Francisco. Tracing City Lights’ history to its present day status allows one to see that although City Lights seems to cling to their Beatnik past, they continue to sell and publish books that challenge all of us in their own unique and important ways.

“A Literary Meeting Place.”

City Lights was founded in one cramped corner of the Artigues Building on Columbus Avenue by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter Martin.  City Lights was the first and only paperback bookstore (“Lawrence”; Emblidge). So right from the get-go with City Lights there was an attempt to connect to the community. Paper-backs were the black sheep of the book world because they were so cheap and thus accessible to everybody, particularly those people not a part of the genteel culture. A booksellers choices about “what books to carry and sell are shaped” by whether or not the seller believes they should be “taking an active role in guiding the reading” of the customers (Miller 55). By choosing to carry only paperbacks Ferlinghetti was, in one way, establishing that his bookstore would be geared toward a more middle-class customer. It is likely that he was giving his customers access to literature that may have otherwise unavailable for them due to the fact that at the time there were a large number of immigrants living in the North Beach area (“North Beach”). Thus in a small way Ferlinghetti was not only reaching out to appeal to his non-genteel neighbors, but was actually ‘guiding’ what his customers were reading much like, dare we say, a traditional bookseller.

City Lights was the first and only paperback bookstore (“Lawrence”; Emblidge). So right from the get-go with City Lights there was an attempt to connect to the community. Paper-backs were the black sheep of the book world because they were so cheap and thus accessible to everybody, particularly those people not a part of the genteel culture. A booksellers choices about “what books to carry and sell are shaped” by whether or not the seller believes they should be “taking an active role in guiding the reading” of the customers (Miller 55). By choosing to carry only paperbacks Ferlinghetti was, in one way, establishing that his bookstore would be geared toward a more middle-class customer. It is likely that he was giving his customers access to literature that may have otherwise unavailable for them due to the fact that at the time there were a large number of immigrants living in the North Beach area (“North Beach”). Thus in a small way Ferlinghetti was not only reaching out to appeal to his non-genteel neighbors, but was actually ‘guiding’ what his customers were reading much like, dare we say, a traditional bookseller.

In 1955 Ferlinghetti launched the Pocket Poets Series which is exactly what it sounds like: paperback books of poetry that are pocket sized. Their size made them affordable poetry books which meant that for the people who bought them this could be their first exposure to alternative types of poetry since it was mostly avant-garde poetry being published. By publishing such  works Ferlinghetti was staying true to his own anarchistic beliefs. As he once put it, “[t]he function of the independent press (besides being essentially dissident) is still to discover, to find the new voices and give voice to them” (“Collection”). These poets that Ferlinghetti published in the Pocket Poets were unable to get their work published by the other, larger publishing houses due to their alternative content. By publishing them Ferlinghetti was staying true to his dissident beliefs about publishing, and adding to the “diversity of literary voices” (Miller 62). Doing so means those voices could be heard not only by their friends but, because Ferlinghetti carried their books in his store, by anybody who picked the book up. Could this be seen as Ferlinghetti, yet again, playing into the traditional view of the bookstore/bookseller as being “an institution that worked to educate and uplift the population” (Miller 58)? Possibly, as he’s not only helping bring counter-cultural literature to his immediate community but also serving the literary community by publishing those books at all.

works Ferlinghetti was staying true to his own anarchistic beliefs. As he once put it, “[t]he function of the independent press (besides being essentially dissident) is still to discover, to find the new voices and give voice to them” (“Collection”). These poets that Ferlinghetti published in the Pocket Poets were unable to get their work published by the other, larger publishing houses due to their alternative content. By publishing them Ferlinghetti was staying true to his dissident beliefs about publishing, and adding to the “diversity of literary voices” (Miller 62). Doing so means those voices could be heard not only by their friends but, because Ferlinghetti carried their books in his store, by anybody who picked the book up. Could this be seen as Ferlinghetti, yet again, playing into the traditional view of the bookstore/bookseller as being “an institution that worked to educate and uplift the population” (Miller 58)? Possibly, as he’s not only helping bring counter-cultural literature to his immediate community but also serving the literary community by publishing those books at all.

November 1, 1956 was when the undoubtedly most infamous Pocket Poets Series book was published: Howl and other poems by Allen Ginsberg. The poems of this book had intense sexual images, drug use and all sorts of things that would be considered less than conforming to uptight 50s standards. The video below is a recording of Allen Ginsberg reading the title poem from the book, which is the best way to experience it, since listening to Ginsberg read the poem at Gallery Six is how Ferlinghetti decided to publish it. In fact, Ferlinghetti sent Ginsberg a telegraph afterwards saying “I greet you at the beginning of a great career. When do we get the manuscript?”

While there was no immediate uproar about the contents of Howl, the condemnation did not wait too long. In March of 1957 a shipment of the books arriving from the producer in England was detained in customs for containing obscene content. Those charges were dropped because the federal authorities refused to support the findings of the officer who detained the shipment. But in June of that same year local San Francisco police arrested and brought up charges against Ferlinghetti for selling obscene literature. Only Ferlinghetti was ever tried because fortuitously Ginsberg was in Tangiers at  the time. Ferlinghetti was backed by the American Civil Liberties Union who brought in pro-bono lawyers and literary experts (literature professors from UC Berkley, book reviewers, etc) to his defense. In a land-mark ruling municipal Judge Clayton Horn declared Howl to have redeeming social value and thus be protected under the First Amendment (Emblidge).

the time. Ferlinghetti was backed by the American Civil Liberties Union who brought in pro-bono lawyers and literary experts (literature professors from UC Berkley, book reviewers, etc) to his defense. In a land-mark ruling municipal Judge Clayton Horn declared Howl to have redeeming social value and thus be protected under the First Amendment (Emblidge).

It’s probably common knowledge among Beat lovers that City Lights and Ferlinghetti were the ones who fought against obscenity for Howl, for the Beats, for us really. What probably isn’t common knowledge is that it was the local cops that arrested Ferlinghetti, because due to the high profile of (and later historical significance of) the case it’s most likely assumed the government or federal authorities were the ones who put Ferlinghetti and Howl on trial. The federal authorities had the chance to attack City Lights but wouldn’t do it. The local cops who Ferlinghetti might have bumped into at the supermarket were the ones who decided to make arrests. This reflects a lack of local support: if the local cops are the ones who wanted to stop the sale of Howl then undoubtedly the surrounding community was unhappy with what was being sold by this bookstore. If a bookseller is supposed to know their “locale by being intimately involved with it,” how involved could Ferlinghetti have been if he was arrested and put on trial by the community in which his bookstore was located (Miller 83)? Years later in the introduction to his book about the trial Ferlinghetti states that the San Francisco Chronicle “started calling [City Lights] the intellectual center of the city” in 1955 before the trial (Ferlinghetti). But in 1959, two years after the trial, in the same paper a journalist wrote about a poetry reading by the Beats stating that “the poems were smartly wild and uninhibited before an audience that could be shocked only by the appearance of a hair oil bottle” (McClure). Was the community conflicted? Had it just changed its’ mind after the trial? Were Ferlinghetti and City Lights just that out of touch with the local San Franciscans?

To be fair to Ferlinghetti it was the 1950s and the beginning of the Cold War. Anything even the slightest bit not conforming to ‘America’ was treated as suspicious and loathsome (see McCarthyism). With On The Road published in 1957 as well there was a rising national sentiment against the Beats. So there could have been pressure from outside forces (government or community based) on the local police to do something about the bookstore. It is also probable that in reality Ferlinghetti did not necessarily have his local community in mind when publishing and fighting for Howl but rather the  larger literary or global community. As opposed to the rising trend of consumerism, selling things, and “accept[ing] no responsibility for the content” Ferlinghetti functioned as an interpreter “between the need of the people of [the] community and the literature of [his] time” (MacLeish 16). The Beatniks life and work were in reaction to the society in which they lived, and clearly with all the work they were churning out their voices were in need of being heard. Ferlinghetti was ready to provide a way to let them be heard. He created a space where “the public [was] being invited, in person and in books, to participate in that ‘great conversation’ between authors of all ages, ancient and modern.” City Lights mission was create a comfortable environment in which the literary enthusiasts of all diverse backgrounds could gather to not only enjoy literature but through writing and reading could push the boundaries of what defined good literature and push back against larger societal standards. A place is simply a place until someone gives a specific meaning to that place (Cresswell 2). Through City Lights, Ferlinghetti was able to create a place that was able to siphon the alternative literature into a space that would resonate throughout the country.

larger literary or global community. As opposed to the rising trend of consumerism, selling things, and “accept[ing] no responsibility for the content” Ferlinghetti functioned as an interpreter “between the need of the people of [the] community and the literature of [his] time” (MacLeish 16). The Beatniks life and work were in reaction to the society in which they lived, and clearly with all the work they were churning out their voices were in need of being heard. Ferlinghetti was ready to provide a way to let them be heard. He created a space where “the public [was] being invited, in person and in books, to participate in that ‘great conversation’ between authors of all ages, ancient and modern.” City Lights mission was create a comfortable environment in which the literary enthusiasts of all diverse backgrounds could gather to not only enjoy literature but through writing and reading could push the boundaries of what defined good literature and push back against larger societal standards. A place is simply a place until someone gives a specific meaning to that place (Cresswell 2). Through City Lights, Ferlinghetti was able to create a place that was able to siphon the alternative literature into a space that would resonate throughout the country.

As MacLeish predicted in his speech to the American Booksellers Association 15 years earlier, there was a return to the bookseller viewing and selling his books as though it were a responsibility with Ferlinghetti, and so there was an “increase in the power and influence of printed books” (MacLeish 17). The ruling of Howl as not being obscene, as having redeeming social value, cleared the way for a multitude of books to be published that could otherwise have been lost to the literary community, and us all. While many of us would hesitate to call Ferlinghetti traditional, all of this does imply that Ferlinghetti and the others working at City Lights fall into the purview of a traditional bookseller. But if the traditional bookseller is one that’s going to unabashedly sell and publish works that not only challenge the dominant culture and expose all its ills, maybe that’s exactly what we need.

“Where the Streets of the World Meet the Avenues of the Mind.”

The intersection of  Broadway and Columbus is almost precisely where Chinatown and North Beach meld together. This intersection also happens to be the home of City Lights Bookstore. When two such varied entities come together in one place, the community that is created is an especially unique one. Today North Beach has retained much of its infamous Beatnik roots, as well as its predominantly Italian-American population. This influence was easy to spot, given the numerous Italian restaurants such as Nizario’s Pizza and E Tutto Qua. The Beatniks are also represented in this part of the city with bar’s such as the Vesuvio Café located on Jack Kerouac Alley and only two blocks from the Beat Museum. There is a prevalence of adult clubs, such as the Roaring 20s and the Condor Club a hallmark of the red light district that North Beach is also identified with. Chinatown is also well represented in this small radius, in the form of multiple Asian restaurants including the Bow Bow Cocktail Lounge, New Sun Hong Kong, and Tutti Melon.

Broadway and Columbus is almost precisely where Chinatown and North Beach meld together. This intersection also happens to be the home of City Lights Bookstore. When two such varied entities come together in one place, the community that is created is an especially unique one. Today North Beach has retained much of its infamous Beatnik roots, as well as its predominantly Italian-American population. This influence was easy to spot, given the numerous Italian restaurants such as Nizario’s Pizza and E Tutto Qua. The Beatniks are also represented in this part of the city with bar’s such as the Vesuvio Café located on Jack Kerouac Alley and only two blocks from the Beat Museum. There is a prevalence of adult clubs, such as the Roaring 20s and the Condor Club a hallmark of the red light district that North Beach is also identified with. Chinatown is also well represented in this small radius, in the form of multiple Asian restaurants including the Bow Bow Cocktail Lounge, New Sun Hong Kong, and Tutti Melon.

View City Lights Booksellers & Publishers in a larger map

In terms of demographics, this area of San Francisco is lower income. The average household income is around $12,500, with 25% of residents below the poverty level. The level of education for this area is also below the California averages. Over half of the population of this area identifies as Asian, with the next largest majority being Caucasians, along with a small amount of Hispanics, and even smaller percentage of African-Americans.  Now, knowing a lot more about the physical area of North Beach/Chinatown the question then becomes what are the people like, and how does a predominantly alternative oriented bookstore connect to such a diverse community?

Now, knowing a lot more about the physical area of North Beach/Chinatown the question then becomes what are the people like, and how does a predominantly alternative oriented bookstore connect to such a diverse community?

As Laura Miller notes in her book The Reluctant Capitalist, “…community connotes the small social realm…community implies social bonds based on affective ties and mutual support…and community evokes a past steeped in tradition as opposed to a constantly changing present”(119). If we take this definition of community, then City Lights can be considered successful in their endeavor to create a community within the bookstore, as well as becoming part of the local community. Beat culture is still relevant to this day, and the literature associated with the movement is still influential. City Lights has retained the same counter cultural and alternative style that it had when Laurence Ferlinghetti first founded it. In that sense, they have continued to support the same group/community of people that desire to learn more about alternative literature. This community, though, is not only in the immediate physical area, but has extended to include the many people that visit San Francisco to see City Lights for themselves. That is how City Lights creates meaning in their place for one group of people, but how do they turn place into space for other members of the immediate community? That answer can be found in the actual stock of books in City Lights. For example, they stock such genres as Asian-American writing, African-American writing, San Francisco literature and history, and Gay and Lesbian. The bookstore is reaching out into the community in order to show how they wish to connect to the varied aspects of the people around them based on their interests.

The City Lights masthead describes it simply as a ‘literary meeting place,’ and this simple meeting place has, for many years, become a gathering place for people not only interested in the type of books being sold, but the type of culture and artistic expression that can be found there. A place is simply a place until someone places a specific meaning in that place, and only then does it become a space (Cresswell 2). Any other bookstore established in that area would be just another bookstore. But with its connection to the Beat generation, and its history of supporting alternative cultures and ideas, City Lights creates a specific space that people are drawn to. This space then influences the spaces around it, as is evidenced in the types of businesses that surround City Lights that cater to the groups of people likely to frequent this alternative bookstore. As globalization overtakes many independent bookstores, City Lights has remained a bastion of not only the emotional attachment associated with place, but preserving the meaning people of this area have attached to it (Cresswell 10). If “place is also a way of seeing, knowing and understanding the world” City Lights is able to preserve for the consumer an understanding of what was alternative in the past, and exemplifies what is alternative in our present culture (Cresswell 11).

“A Kind of Library Where Books are Sold.”

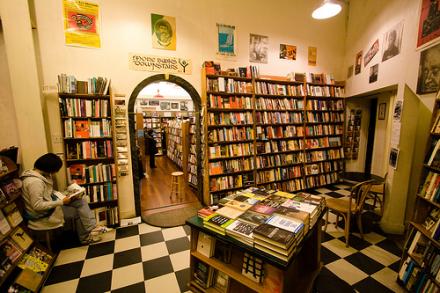

Through the front window of the triangular Artigues Building one can see shelves upon shelves of books inside City Lights Bookstore. This front room of the three floored bookstore is the main Fiction Section. City Lights claims to have the “finest fiction by American, English, and European writers, magazines and journals, and art books,” as they display on their website. Like chain bookstores, it has some tables and shelves for big name publishers to display their hardcover books, but like an independent bookstore, City Lights prides itself in offering books from less well-known small presses and specialty publishers. By supplying all of these books, City Lights can serve their specialty niche market, while still appealing to any of the locals who visit the store and are not as interested in City Light’s “alternative literature.”

Through the front window of the triangular Artigues Building one can see shelves upon shelves of books inside City Lights Bookstore. This front room of the three floored bookstore is the main Fiction Section. City Lights claims to have the “finest fiction by American, English, and European writers, magazines and journals, and art books,” as they display on their website. Like chain bookstores, it has some tables and shelves for big name publishers to display their hardcover books, but like an independent bookstore, City Lights prides itself in offering books from less well-known small presses and specialty publishers. By supplying all of these books, City Lights can serve their specialty niche market, while still appealing to any of the locals who visit the store and are not as interested in City Light’s “alternative literature.”

The far right side of the first floor is known as the “Third-World Fiction Room.” Here are books written by writers from Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and the Caribbean and Pacific Islands can be found, along with many self-published books from these sorts of writers.  The basement is the Nonfiction Section. Here one can find all the usual Nonfiction categories: Philosophy, Religion, etc. City Lights also has unique categories like Muckraking, Commodity Aesthetics, Topographies, Evidence, People’s History, Class War, Stolen Continents, and other categories one wouldn’t find anywhere else. These are the categories that really help show what City Lights is all about. Their ideal reader base would be into books about alternative ideas, much like the ideas one would find in these categories. If City Lights is so proud to have this literature, why would they hide it in separate sections from the other books? Maybe City Lights wants to glorify these sections. They are on a different level of importance than the other books, thus they deserve their own rooms.

The basement is the Nonfiction Section. Here one can find all the usual Nonfiction categories: Philosophy, Religion, etc. City Lights also has unique categories like Muckraking, Commodity Aesthetics, Topographies, Evidence, People’s History, Class War, Stolen Continents, and other categories one wouldn’t find anywhere else. These are the categories that really help show what City Lights is all about. Their ideal reader base would be into books about alternative ideas, much like the ideas one would find in these categories. If City Lights is so proud to have this literature, why would they hide it in separate sections from the other books? Maybe City Lights wants to glorify these sections. They are on a different level of importance than the other books, thus they deserve their own rooms.

The second floor of City Lights contains the Poetry Room, housing all of the poetry City Lights has to offer. To even get to the Poetry Room in City Lights, you have to either know where it is or see one of the signs that says “Poetry and Beat Literature Upstairs,” pointing to the stairs. The stairwell that leads upstairs is buried in the back of the main level. Without the signs one would probably look at the stairwell and think it was off-limits. Nonetheless, this is one of the most notable places in City Lights. Because of this, we have provided an estimated floor plan to give an idea of what the atmosphere in the Poetry Room looks like.

The second floor of City Lights contains the Poetry Room, housing all of the poetry City Lights has to offer. To even get to the Poetry Room in City Lights, you have to either know where it is or see one of the signs that says “Poetry and Beat Literature Upstairs,” pointing to the stairs. The stairwell that leads upstairs is buried in the back of the main level. Without the signs one would probably look at the stairwell and think it was off-limits. Nonetheless, this is one of the most notable places in City Lights. Because of this, we have provided an estimated floor plan to give an idea of what the atmosphere in the Poetry Room looks like.

From the floor plan above, one can see that unlike the main floor, the Poetry Room is not stuffed with books, but feels more snug, like a nook for reading away from the eyes of the public. A sign on the wall near one of the poetry shelves proclaims, “Have a seat and read a book.” The space feels more meditative than the more consumer driven first floor (as consumer driven as an alternative bookstore can be, that is).

Being the Poetry Room, this section contains the poetry City Lights has to offer. However, it also contains the Beat Literature and City Lights Publications. This is also the space where many of City Lights’ events and readings are held. It appears to be a very important place for City Lights, so why would they keep all of this important work on the second floor?

A basic way of interpreting this is that poetry and Beat Literature are considered above all the other types of literature carried in the store, as with the Third World Fiction and the Nonfiction, so they are elevated and placed away from the other literature. If a person getting “an old book is its rebirth” this means that us readers give a book its meaning and cultural context.

Then the books of poetry and the Beats are, by the placement of their shelves being upstairs, more important (Benjamin 61). Or, maybe City Lights is trying to keep these books away from the casual reader. It could be like Roger from Christopher Morley’s Parnassus on Wheels, where City Lights is keeping books away from those who aren’t ready for them yet. Whatever the reason, City Lights still shows that this is the literature that matters: the poetry, their publications, the Beat Literature that got them started. However, one needs to be part of their “little club” of like-minded readers before they can fully enjoy what City Lights has to offer. They have to know to go upstairs. They have to be ready for what City Lights and the Beats had to offer.

Being a bookstore filled with alternative literature, City Lights manages to capture the feel of a specialized independent bookstore. It is filled with bookshelves so close together that it must be cramped and hard to move around. City Lights wants to be the place where you can see books everywhere. It is much like what Miller talks about in Reluctant Capitalists. “Common to many bookstores,” she writes, “are the tables and chairs that are scattered about the premises. With these, customers are invited to settle in for a good read or chat with friends” (Miller 125). Chairs are placed all around, and signs urging people to think and read hang on every wall. Miller also describes why people frequent independent bookstores: because they can get more than just a book, they can get a community experience (Miller 121). From the layout of the store, this definitely seems to be what City Lights is aiming for. In the end though, is this what City Lights has managed to do? Have they created a welcoming atmosphere for their North Beach community, or just their little clique? Maybe City Lights has only created a community for their books. Like Latour says, City Lights is trying to make matters of concern into matters of fact, or open people’s eyes to the fact that there are important issues we should all be paying attention to. With City Lights’ huge collection of alternative and counter-cultural literature, it is hard not to see them in this light. Is this the kind of literature the community wants, or just the literature the bookstore wants? Whichever one, City Lights has managed to keep going for years and years, where other bookstores have not, and it does not seem like City Lights will be leaving the North Beach community anytime soon.

“Sixty Years in the Kingdom of Books.”

City Lights started modestly, though not unassumingly. Carrying all paperbacks was just the start of their mission to promote alternatives to mainstream society, using all types of literature to accomplish this. They became famous for it with Howl, and today the varying sections of fiction in the store continue this counter cultural legacy. Maybe they don’t appeal that much to the local community. Maybe they try to separate the run-of-the-mill Beat tourist from the dedicated counter cultural reader through the organization of the store. That being true, what matters more is that the alternative literature is out there being read, and the issues of today’s world are being heard, and not merely silenced or censored. City Lights understands the role and responsibility it has as a bookseller; a responsibility to provide the literature that people may not be ready for, but that they need.

Bibliography:

Text–

Benjamin, Walter. “Unpacking My Library”. Illuminations. Shocken Books: New York. 59-67.

Brown, Bill. “Thing Theory.” Critical Inquiry Vol. 28, No. 1. p 1-22.

“Collection: City Lights Pocket Poets.” City Lights Bookstore. http://www.citylights.com/collections/?Collection_ID=305

Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub, 2004.

Emblidge, David. “City Lights Bookstore: ‘A Finger in the Dike.’” Publishing Research Quarterly. December 1, 2005 .

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence. “Howl on Trial: The Battle for Free Expression.” City Lights Publishers. San Francisco, California. 2006.

Latour, Bruno. “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam?” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. 2nded. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010. 2282-302.

“Lawrence Ferlinghetti.” City Lights Bookstore. http://www.citylights.com/ferlinghetti/

MacLeish, Archibald. “A Free Man’s Book.” Annual Banquet of the American Booksellers Association May 6th 1942. Mount Vernon, New York: The Peter Pauper Press.

McClure, Donavan. “Beat Poets Appear En Masse–A Mess.” San Francisco Chronicle. 24, May 1959. Web. November 2013.

Miller, Laura J. Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Morley, Christopher. Parnassus on Wheels. New York: Avon Books, 1983.

“North Beach.” Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Beach,_San_Francisco

Images–

Google Images: City lights, beat generation. <google.com>

<http://citylights.com>

Video–

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MVGoY9gom50>

0 Comments