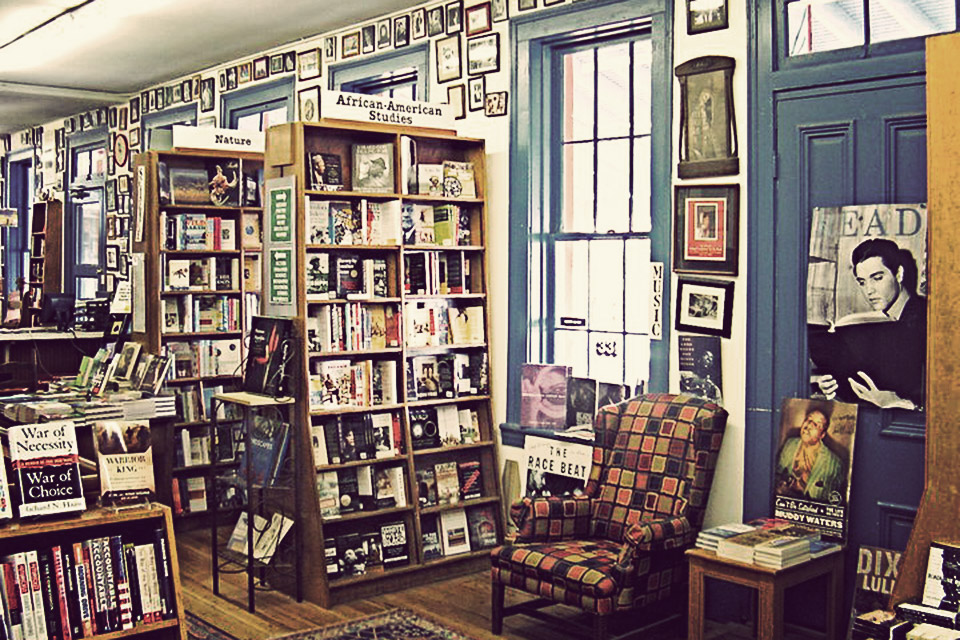

Taking a look at the walls of the main storefront of Square Books, located in The Square, Oxford’s iconic town center, it seems fair to say that if Richard and Lisa Howorth are the bricks that keep the bookstore standing, then the award-winning authors who consider themselves “friends of the store” are the wallpaper. Quite literally. Peering down over shelves brimming with paperbacks and packed hardcovers are the often-signed portraits of authors ranging from Richard Ford to Etheridge Knight. In crooked rows they cover the white space of hallways, framing windows, livening doors, and offering a rush of faces on the wall of the staircase going to the second floor. In her autobiography Sunwise Turn, bookseller Madge Jenison once described the way she made “a collection of several thousand customers—a kind of museum of portraits and attributes and personality” (117). The Howorths have taken this metaphor a step further, lovingly rendering a visual display of the authors who have walked Square Books’ hardwood floors. From their perches, these authors watch people move through the store, counting footsteps, tasting the same literature in the hands of the customers, and the Howorths, or at least it would seem, watch back.

According to journalists, whose tales of nights sitting around the Howorth dinner table feature all the intrigue and curiousness of gossip, the Howorths “basically run a B&B for writers.” In their guest bedroom, a quaint room furnished with antique beds Ms. Howorth once discovered at a flea market, it is not uncommon to find award-winning writers happily sleeping away the night, with the likes of Ann Patchett, Donna Tartt, and Richard Ford being fabled as recent guests. Nightly entertainment, at least according to the Howorth daughter, often includes road trips through the Mississippi Delta and thirty-mile drives to a juke joint once owned by famed blues musician Junior Kimbrough. As the Howorth daughter describes of the Southern-hospitality inclinations of her parents, “what’s 30 miles when you have a car and a bottle of bourbon?” Yet, at its root, the Howorths’ hospitable attitude towards the authors they host seems to be more complex than the simple seeking-out of pleasure. They seem to reflect scholar Doreen Massey’s propositions that place, in a world where all communication is “spreading out” (63), must be considered with a more complicated view. As she asks us to envision, “imagine not just all the physical movement, nor even all the often invisible communications, but also and especially all the social relations, all the links between people” (68-69). In focusing their attentions on building author relationships that are more indicative of deep friendships than professional bonds, the Howorths seem to be growing their own social network of writers. On the walls of Square Books these relationships are given physical representation in black and white and sepia tones, making the Square Books storefront into a place that both acknowledges the “physical movement” of these authors as well as the deep bonds of “social relations” that keep them ever-watchful over Square Books’ success.

But before the Howorths were entertaining guests from their living room or shellacking signed portraits to their walls, they spent the better part of 1977 and 1978 in self-commissioned exile in Washington D.C. To better understand the business of selling books, they spent their days working with Savile Book Shop, a once-bustling bookstore in Georgetown that was floundering under poor management. Early in 1979, as Savile Book Shop was preparing to close its doors, the Howorths moved back to Richard’s hometown of Oxford, Mississippi and opened the first Square Books storefront on the upper floor of a building overlooking The Square. The origins of this first storefront were humble, made possible by $10,000 the Howorths had saved and $10,000 they borrowed from the bank.

In October of 1979, Square Books welcomed its first visiting writer. Reading from her recently published novel The Rock Cried Out, Ellen Douglas’ presence in Oxford shepherded in a line of authors willing to give readings and host book signings out of the storefront. By the time Mississippian poet Etheridge Knight came to read by the later part of 1979, Square Books had already established itself as a bookshop welcoming authors with open arms. In speaking to the cultural network of literature, Christopher Morley once proposed that the “vibrations that great books and the personalities behind them set up, may travel a surprisingly long way” (61). Though the mysterious power of Morley’s literary vibrations, along with a good amount of luck, might be partly responsible for the success of Square Books and the authors it shepherded, the Howorths were quick to manipulate the cultural networks they saw growing in their community. Corresponding with Square Books’ opening was the founding of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, funded by the nearby University of Mississippi (Ole Miss). Bill Ferris was quickly elected as the first director, overseeing a regional studies program that was the first of its kind in the country, focusing on a study of the American South. Square Books happily became a pinnacle part of the Center’s public outreach initiative, offering to host readings, all heralded by Bill Ferris, of literary greats like Allen Ginsberg, Alex Haley, Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker.

Just like that, Square Books’ social network was growing, with Richard and Lisa Howorth counted among their friends many titans of the industry. By 1980, Willie Morris was signing on to become a Writer-in-residence at Ole Miss. An author and editor with a reputation for unabashedly exploring subject outside the attentions of mainstream presses, including issues of segregation, illiteracy, and nursing home conditions, he quickly drew the edgy aesthetics of authors like James Dickey, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton to Square Books. Their visits culminated with a reading by William Styron, writer of literary darling Sophie’s Choice, whose presence drew such a large crowd of people to the store that the line wrapped around the street corner. Whether by the magic of Morley’s vibrations or the Howorths’ elbow grease as they invested themselves in the burgeoning cultural networks of their community, by 1982 Oxford, Mississippi, and Square Books in extension, was being hailed as a literary Mecca. By the time Barry Hannah settled into Ole Miss as a Writer-in-residence, students like Donna Tartt were flocking to the area, accompanied by already-established writers like Amy Hempel and Richard Ford.

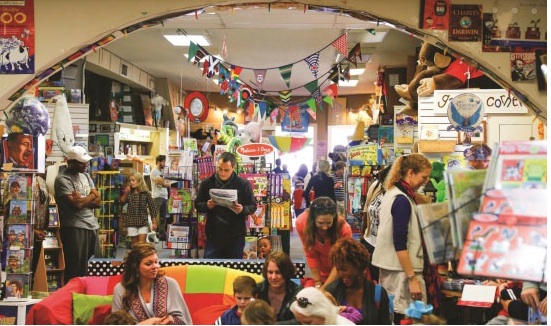

Now feeling cramped by the confines of the small upstairs space, Square Books changed locations in 1986, moving just under 100 feet from their original location into a historic two-story building with a central location on The Square. Business promptly doubled. The crowds forced the Howorths to open an annex store, Off Square Books, in 1993, where they moved their lifestyle volumes and vast collections of used and remainder books. In 2003 Square Books grew for the final time with the opening of Square Books Jr., specializing in children’s literature and educational puzzles and toys.

In speaking to the state of contemporary bookselling, Laura Miller argued that “The homegrown bookstore, it is said, is more attuned to local tastes and also has the flexibility to respond to community variations” (83). If nothing else, it seems as though an awareness of the opportunities and social networks of its community has defined the history and modern successes of Square Books. Quickly adapting to the ever-changing slew of authors walking the streets of Oxford by developing friendships in the name of Southern hospitality, the Howorths have developed Square Books into a literary hub in the middle of what was once a quiet college town. Yet seldom do successes of this magnitude come without costs. The Howorths are open about the negative effects their successes has had on the Oxford community at large, citing “inflated housing prices, big-box retailing on the town’s periphery, and development pressure on the square itself” (Gurwitt). Over the last two decades, Lafayette County, the county in which Oxford lies, has become the fastest-growing county in Mississippi, partly due to an influx in tourist traffic. In 2001, Richard Howorth submitted a last-minute mayoral bid in an effort to forestall an Oxford partnership with corporate retailer Wal-Mart that would widen roads into Oxford in an effort to increase traffic through the megastore’s doors.

Even as Richard Howorth publicly rises against the corporatization of the Oxford area which is an open symptom of local successes like his, he seems to have difficulty positioning himself, as well as the three locations of Square Books, in discussions of corporatization and commodification. The original storefront of Square Books remains the cultural hub of the empire, while Off Square Books and Square Books Jr. operate in the shadow of their predecessor, seeming like book warehouses in comparison. Though they still retain all the charm and artsy aesthetic indicative of independent booksellers, there is something largely absent from the walls. Look there. What do you see? A brick wall. Colorful paintings. But where are the authors, looking over your shoulder? Where are their signatures? Where are their fingerprints on the glass of their portraits?

The answer? They’re over in the original Square Books.

Works Cited:

Photographs-

N.d. Blogspot Blog. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://3.bp.blogspot.com/–Kscy10Cc1Q/VQYhOeJAAaI/AAAAAAAADms/RZg8shNWRns/s1600/IMG_3260.JPG>.

N.d. From The Mixed Up Files. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.fromthemixedupfiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Square-Books-Jr.-Interior-3.jpg>.

N.d. From the Mixed Up Files. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.fromthemixedupfiles.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Square-Books-Jr.-Interior-3.jpg>.

N.d. Gallivant. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://gallivant.com/p/2013/08/square-books-3.jpg>.

N.d. Oxford, Mississippi. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://oxfordmississippi.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/upstairs-square-books-oxford1.jpg>.

N.d. Square Books. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.squarebooks.com/sites/squarebooks.com/files/Off_SB__B_W_photo_.jpg>.

N.d. Square Books. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.squarebooks.com/sites/squarebooks.com/files/SquareBooksJr_0.jpg>.

N.d. Vanity Fair. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://media.vanityfair.com/photos/54cc041244a199085e89cefa/master/h_606,c_limit/image.jpg>.

Sources-

“About – Center for the Study of Southern Culture.” Center for the Study of Southern Culture. University of Mississippi, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://southernstudies.olemiss.edu/about/>.

Bales, Jack. “Willie Morris.” The Mississippi Writers Page. The University of Mississippi English Department, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://mwp.olemiss.edu//dir/morris_willie/>.

Chamberlin, Jeremiah. “Inside Indie Bookstores: Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi.” Poets & Writers. Poets and Writers, 1 Jan. 2010. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.pw.org/content/inside_indie_bookstores_square_books_oxford_mississippi?cmnt_all=1>.

Cresswell, Tim. Place: An Introduction. N.p.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004. Print.

Guajardo, Rod. “Lafayette County Shows Highest Percentage Growth in State.” Oxford Citizen. Oxford Citizen, 04 Apr. 2015. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://oxfordcitizen.com/2015/04/04/lafayette-county-shows-highest-percentage-growth-in-state/>.

Gurwitt, Rob. “Richard Howorth: Bibliocrat.” Governing: The States and Localities. E. Republic, Aug. 2001. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.governing.com/topics/politics/Richard-Howorth-Bibliocrat.html>.

“A History of Square Books.” Square Books. Square Books, n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.squarebooks.com/history>.

Jenison, Madge. Sunrise Turn. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1923. Print.

Kurutz, Steven. “The Yoknapatawpha Salon and Inn.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 24 Dec. 2008. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/25/garden/25square.html?_r=0>.

Morley, Christopher. Ex Libris Carissimus. New York: A.s. Barnes, 1932. Print.

Rosen, Judith. “Square Books Named ‘PW’ Bookstore of the Year; Miller Rep.” PublishersWeekly.com. Publishers Weekly, 01 Apr. 2013. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/bookselling/article/56618-square-books-named-pw-bookstore-of-the-year-miller-rep.html>.

Winburne, Peggy Reisser. “A Literary Light In Oxford, Mississippi: The Square Books Story.” WKNO 91.1. NPR, 17 May 2013. Web. 24 Feb. 2016. <http://wknofm.org/post/literary-light-oxford-mississippi-square-books-story#stream/0>.

0 Comments