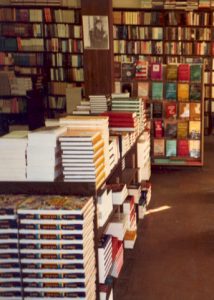

Photographs of my father’s bookstore in Judaica Book News and The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles reveal the care he took to arrange and display his books, the meticulous presentation of his collection. Yet just as important to the store’s outward face was its inward floor plan, which reflected a certain narrative about the collection.

Below is a floor plan of the store. If you hover over the image, small icons will pop-up.

- Green icons indicate text

- Red icons indicate image

- Begin at the entrance and go clockwise

Following the books in this direction, customers were clearly led from the past to the present, from a Jew’s foundational reading toward works that, in some ways, depended on previous knowledge to contextualize their Jewishness. Traversing the store from the opposite direction simply turned such a pedagogical narrative into an archaeology of Jewish writing. Each wall could also be read in itself as a minor commentary on Jewish literature; most evocative was the far wall, which was telling in its reflection of my father’s and, by extension, of publishers’ thinking about the historical succession of Jewish writing: Bible, History/Holocaust/Zionism, Philosophy/ Jewish Thought, Fiction/Poetry, and Yiddish/Cookbooks—a spatial narrative whose punch line is “So now let’s eat.”

One of my own photographs of the store also reveals a prominent and very telling detail of the store’s presentation. Rightward from the entrance, at the far end of the new-book table, was a large support column on which hung a sepia-tone photograph of a bearded old Jew in an old-fashioned, wide-brim biberhit, a beaver hat. He is leaning on a shtender, a lectern, in front of a Torah ark and looking straight into the camera. That was my great-great-grandfather, Dovid Roth. His is an image of Jewish memory and authenticity that privately advertised my father’s ownership of the collection and publicly advertised its cultural purpose. It also turned the customer into the object of a Jewish gaze.

Given the composition of the photograph and its placement just above eye level, my great-great-grandfather functioned as a kind of store greeter, welcoming and surveying all who came in. His regard and appearance assured customers, especially new ones in search of a title like Hayim Donin’s To Be a Jew or Morris Kertzer’s What Is a Jew?, that they were in the right place. What I am suggesting here is that the consciousness that Walter Benjamin, in his essay “Unpacking My Library,” attributes to a collection—a consciousness that is both an extension and reflection of the owner’s mind and tastes (67)—finds symbolic expression in this photograph of a forefather. It illustrates the nature of my father’s “living library” as Benjamin describes a book collection (66): seeing and being seen within a space organized under this sign of memory and by the memory-driven spatial narratives of the store’s floor plan created a metaphoric Jewish community where both the books and the customers were subjects and objects, actors and acted upon insofar as each took possession of the other.

To put it plainly, Jewish memory and Jewish identity accrued social meanings through the customer’s interactions with the store’s collection. Benjamin helps us to see that J. Roth/Bookseller offered customers an opportunity to peruse and possess the personal recollections, creative works, and scholarly interpretations attesting to past and present varieties of Jewish identities and historical experiences. It offered them, in other words, an opportunity to define and be defined by their own Jewish collections. Or, to borrow an insight from James Clifford, the store exemplified that in the modern, consumer-oriented West, collecting things is an extension of “the idea that identity is a kind of wealth (of objects, knowledge, memories, experience),” and that the ways we collect objects help remind us “of the artifices we employ to gather a world around us” (218, 229).

The graph below depicts J. Roth Bookseller’s bestsellers (by author and title), which helps illustrate the various kinds of books customers might identify with, and be identified by, by purchasing them at the store.

My father’s bookstore was one such artifice, a space that enabled a certain kind of cultural and self-possession. To shop at the store was, therefore, an engagement in self-definition and self-explanation. It acted out in small, and for purposes that did not require that one identify as Jewish so much as with Jews, the larger dynamic of my father’s quest to gather a meaningful world around himself through a collection of books. This is one reason that the store was perceived as a welcoming space by Jews of every denomination and ideological bent-from Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovitz, the Orthodox chief rabbi of England, to Rabbi Sue Levi Elwell, the Reform rabbi of Leo Baeck Temple in Los Angeles; from Irving Howe to Dennis Prager; and from Barbra Streisand to Wolf Blitzer. They all shopped there. Non-Jews, too, saw it as a welcoming space, especially the evangelical Christians who visited the store in the 1980s in search of the Jewish roots of Jesus.

Sources

Text

Benjamin, Walter, and Hannah Arendt. Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books, 1986.

Clifford, James. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Images

Courtesy of Laurence Roth

0 Comments